Context is Everything

And a story about bridges

I’ve been meaning to write about this topic for a while. But my post-fire-related musings have been distracting. A post today, however, by the always inspiring Carl Hendrick has given me fresh resolve!

First a story. One with which I open almost every workshop or presentation I give on learning science and learning engineering.

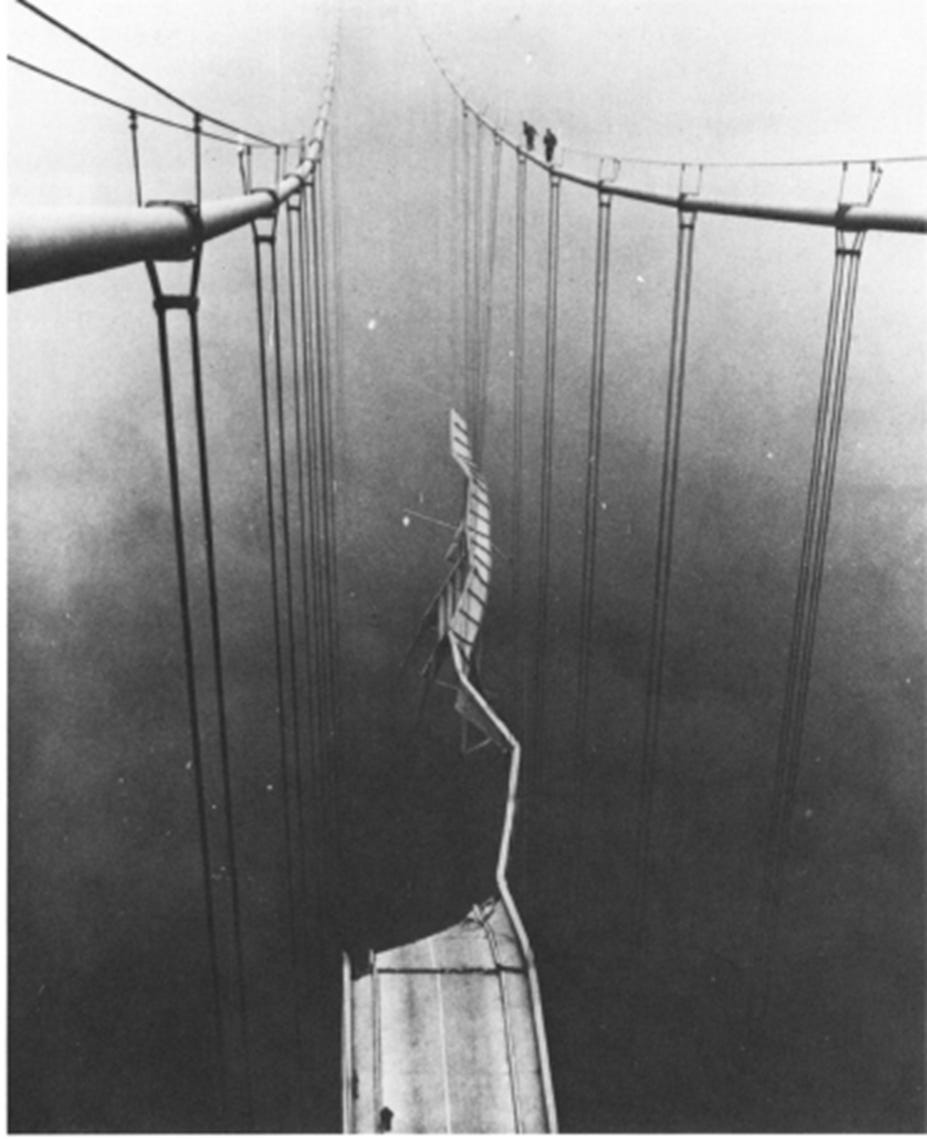

This is the Tacoma Narrows Bridge stretching across the Puget Sound in Washington State. Built in 1940 it was called a triumph of ingenuity and perseverance.

Unfortunately, four months after it opened the bridge collapsed in a windstorm

And went from being a triumph of ingenuity to “the most dramatic failure in bridge engineering history…”

Although incredibly dramatic, there were (amazingly) no human casualties, but there was one victim of the collapse.

Tubby a three-legged cocker spaniel who, following his unfortunate death, became something of a celebrity in the local area and came to symbolize the drama of the day.

So what happened?

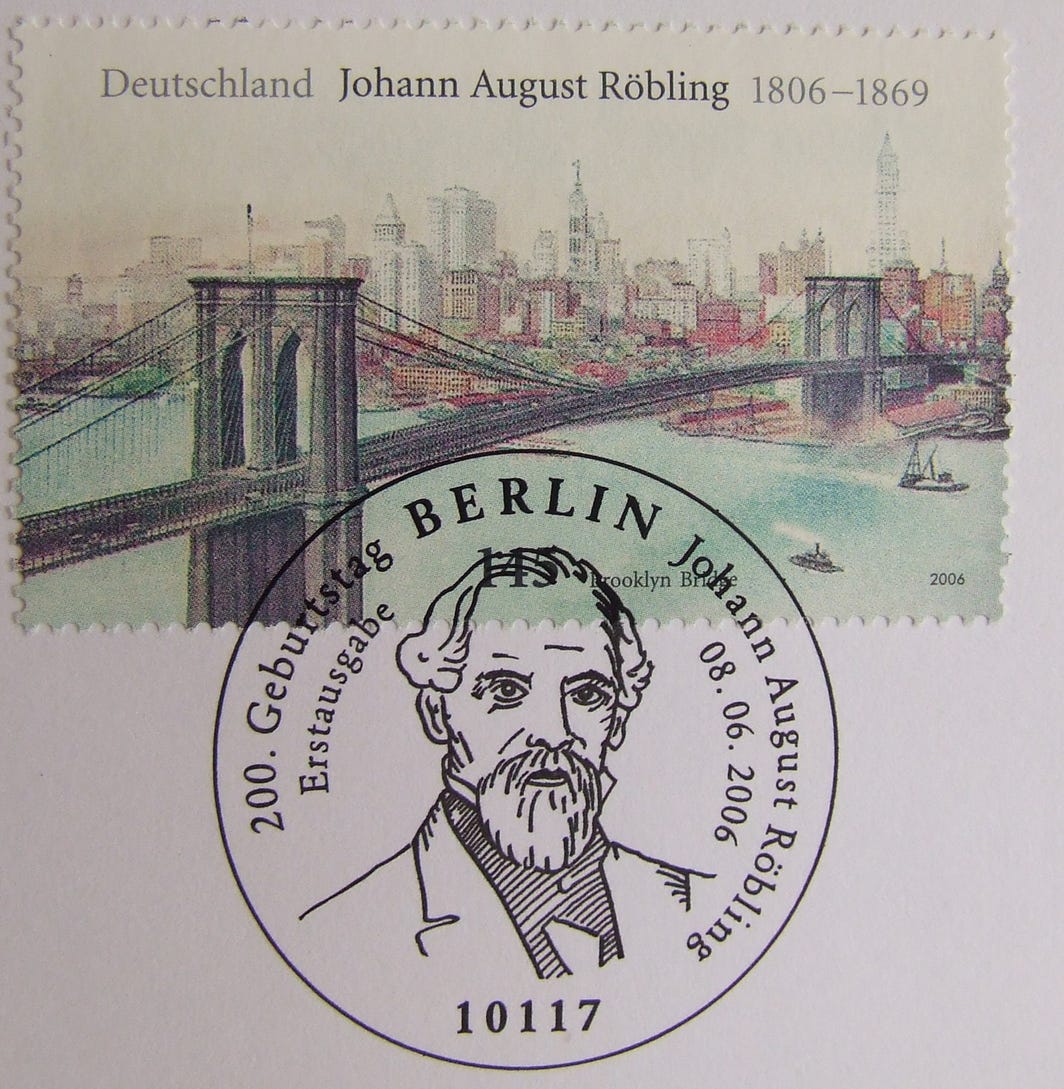

The bridge wasn’t the first of its type. Nor the longest, or heaviest. To answer the question of what happened, we need to look to this guy, John Roebling.

John Roebling was a civil engineer and bridge expert.

A hundred years before the Tacoma Narrows Bridge collapse, there had been many bridge construction failures and a lot of debate over the overall safety of suspension bridges.

Wanting to figure it out, Roebling studied these failures and came up with a formula with three basic principles to guide the construction of safe bridges.

“First, a bridge must be of sufficient mass and inertia to quell excessive wind excitation.

Second, since the wind can either lift up or push down on the bridge, the structure must have stays tying down its deck, either deck to ground or tower to deck.

Third, to be adequately stiff, the bridge must have trusses.”

(Wind Wizard by Siobhan Roberts, Princeton University Press, 2013)

The focus of Roebling’s formula were design features to address the biggest risk to suspension bridges—wind. And he built a number of bridges (including the Brooklyn Bridge) successfully using this formula.

In the aftermath of the collapse many theories were discussed as to why it happened. Ultimately it was determined that the failure was due to the interaction between the bridge’s design and the wind in the Narrows.

The bridge designers knew how to design a bridge. They knew how to find people to build the bridge. It turns out knowing HOW is not enough.

The mistake the original designers made?

They designed the bridge without considering the context in which it was being built. And they designed the bridge without consulting an engineer with expertise in this area, or following the tried and true formula developed by Roebling who had experience building this type of bridge in this type of windy environment.

The mistakes that the bridge designers made are the exact same kind of mistakes that people make when designing learning experiences and environments. They oftentimes ignore (or aren’t aware of) the learning science evidence we have about what works, in which situations, and why!

This happens all the time!

We might know HOW to teach methods for solving equations, but do we know how to do it for students who think they can’t do math?

We might know HOW to teach someone to make an souffle, but can we do so with a group of boys who think “cooking is for girls”?

We might know HOW to create a compliance course that satisfies state requirements for workplace harassment, but do we know how to do that for a group of recent high-school grads working in a supermarket?

The mistake?

We design learning experiences without considering the context.

Without consulting a learning engineer!

Some years ago, I was working on a study that involved training teachers how to use Smart Boards ( a new innovation at the time). Teachers received some extensive training in how to use the Smart Boards in their classrooms and then were returning to their school to put into practice all the cool new things they had learned.

When we called the teachers the following week to see how things were going, and if students liked the Smart Boards, we were surprised to hear—things weren’t going so well.

We scratched our heads. The teachers knew how to use the Smart Boards. They had content to use within the Smart Boards. So what was the mistake that we made?

The teachers were unable to implement the cool new Smart Boards because they had no internet connectivity in their classrooms.

And to make matters worse, to fix the problem involved some complicated Union rules that were almost impossible to navigate.

Our mistake? We designed the intervention without considering the context.

We had cool technology. We had the wherewithal to help teachers learn how to use it. But that wasn’t enough.

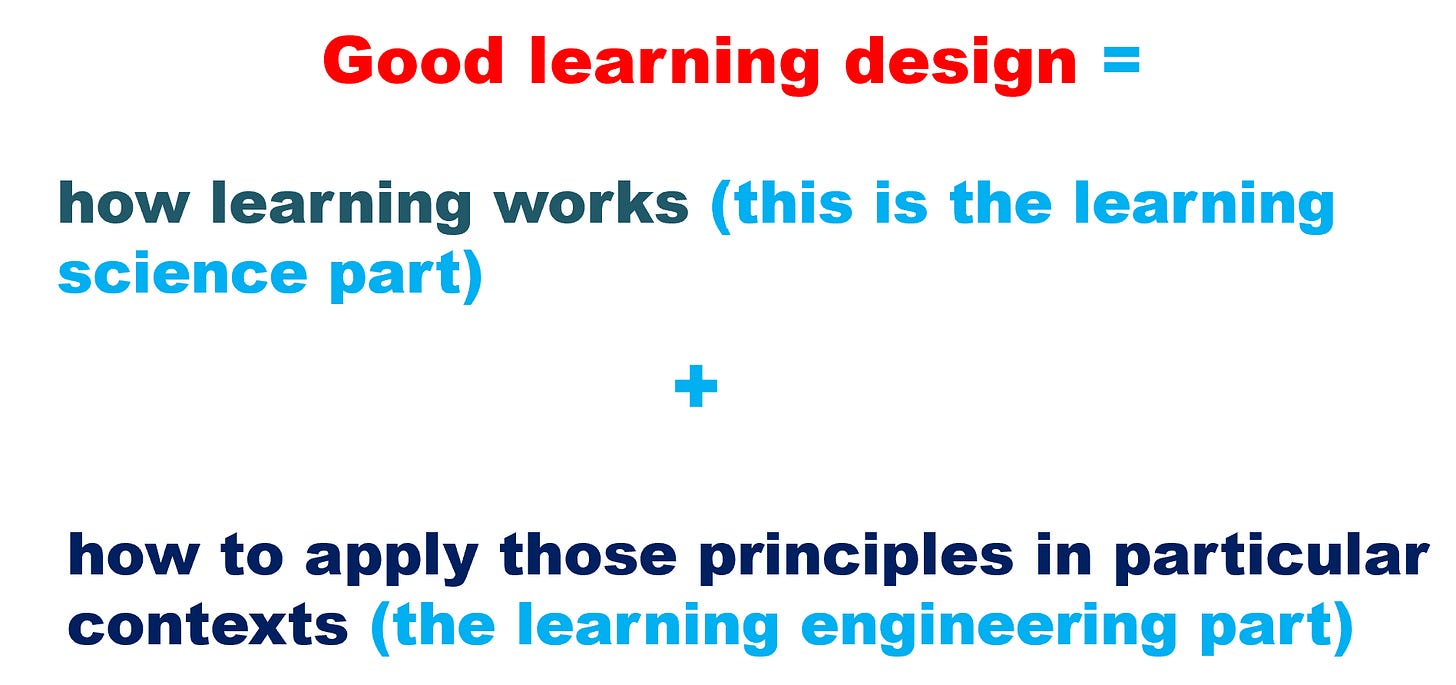

The truth is:

And when we think about context in learning, it’s not about weather conditions, wind, or temperature. It’s so much more complex!

Learners aren’t all starting from the same place. Their experiences, prior knowledge, and motivations are different. They’re not at the same place in in their educational journey. The environment in which they are learning is not the same.

Learners vary.

Teachers vary.

With an understanding of the evidence and scholarship relating to how learning works (including awareness of factors that can impede effective learning), we can design learning experiences that help keep learners engaged, paying attention, motivated, inspired, and on-task.

As we think about our teaching and training strategies and how we design our training and learning experiences there are three things to keep in mind. These are what I consider my “North Stars”:

✨There is not one “go-to solution” for every teaching situation. Understanding this prevents us from putting too much weight on one strategy;

✨Content and pedagogy interact in different ways. Some things may be more or less relevant for you, your classroom, your workplace, your employees, and your particular training modality;

✨A pedagogical tool is only as good as its implementation.

That’s why we focus not just on what to do but how to do it in particular climates and contexts.

So when designing and implementing learning experiences, we have to recognize we not necessarily operating under “ideal” or consistent conditions (just like the environment around this bridge).

We need to figure out how to implement ideas in the real world and understand factors that could get in the way of success, or increase the chance of successful outcomes.

If we don’t, it doesn’t matter how amazing our new learning program, online course, skills training program etc., is, if we haven’t considered the real-world context and constraints we are operating within, all of that innovation is for naught!

If we ignore, as the designers of the failed bridge did, the science and the principles that we know work and in which contexts, our learning efforts are likely to fail.

And we don’t want our learners to end up like Tubby—immortalized by engineering failures!